Over the course of her lifetime, Dickinson wrote hundreds of letters to many different recipients. While she is known for her poetry, Emily Dickinson's letters were also forms of art, the prose just as beautiful and poetic as her official poetry. In fact, these two often coincided because she frequently included poems with her letters or simply wove them into the prose itself to create letter-poems or prose poetry.

In this post, I will examine a few of the recipients of Dickinson's letters, their relationships, and the contents of some of the letters themselves.

SUSAN DICKINSON ("SUSIE")

Arguably one of the most influential friendships Dickinson had during her lifetime, Dickinson's relationship with her sister-in-law, Susan Huntington Dickinson, not only produced beautiful letters, but it also produced a great deal of poetry as well.

Emily frequently shared her poetry with Susan, in which turn, Susan would read and provide feedback on it. Together, in this manner, they edited and rewrote Emily's poetry. We can see this happening in one series of letters, where Dickinson sends one that includes a version of “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers,” to which Sue replies with, “I am not suited dear Emily with the second verse” (Open Me Carefully 98). Because Dickinson and Sue were so close with one another, I believe that Sue was likely able to be more honest with Emily about her poetry than anyone else could be at the time, providing different kinds of feedback than people who simply admired it. It also probably helped that they were neighbors after Susan married Emily's brother, so they would have been able to work on the poetry together outside of their letters.

However, poetry critiques and edits were not all that Dickinson and Sue discussed in their letters––far from it! In fact, some of the most beautiful letters that passed between them were about everyday life. For example, in one letter to Susan, Dickinson opens by writing, “Were it not for the weather Susie – my little, unwelcome face would come peering in today – I should steal a kiss from the sister – the darling Rover returned – Thank the wintry wind my dear one – that spares such daring intrusion!” (Open Me Carefully 7). In this letter, she not only plays with the formatting (capitalization of different words, underlining, and dashes) as she does in her poetry, but she also whimsically plays with words and nature in a way that faintly echoes the style in her poems (“Thank the wintry wind… that spares such daring intrusion”). More lovely prose of this sort about daily life can be found in a later letter, where Emily addresses how much Sue is missed in Amherst and creates beautiful imagery by writing, “It is pleasant to talk of you with Austin – and Vinnie and to find how you are living in every one of their hearts, and making it warm and bright there – as if it were a sky, and a sweet summer’s noon” (Open Me Carefully 43). This remark is not only a precious way for Dickinson to tell Sue that she is loved and missed by the Dickinson family, but it also is a lovely simile––likening Sue’s influence on their hearts to the warm, summer sky.

Furthermore, many moments of humor also appear in Emily’s correspondence with her ‘dear Susie.’ One notable moment of humor is found in a letter where Emily shares a discussion she had with her sister Vinnie about growing old, and she makes the amusing comment, “I do feel gray and grim, this morning, and I feel it would be a comfort to have a piping voice, and a broken back, and scare little children” (Open Me Carefully 11). Reading funny comments like this in her letters better helps me to see yet another side of Emily Dickinson that I previously did not notice.

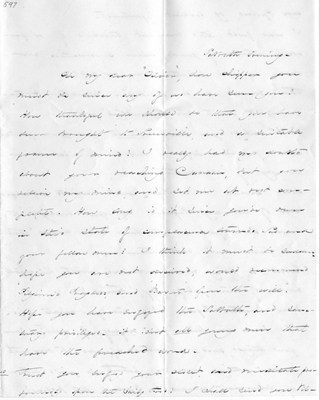

Sadly, not every letter that passed between Dickinson and Susan contained happy content. For instance, one that stands out is a letter that addresses Dickinson’s familiarity with loss. In this letter, Emily writes to Sue, “You need not fear to leave me lest I should be alone, for I often part with things I fancy I have loved – sometimes to the grave, and sometimes to an oblivion rather bitterer than death … Few have been given me, and if I love them so, that for idolatry, they are removed from me” (Open Me Carefully 67), showing that loss is a theme that Dickinson is not only familiar with, but she is also willing to discuss it plainly. In this letter, she beautifully blends the poetic with the practical, creating a rather romanticized-sounding view of loss while simultaneously letting her sister-in-law know that she is used to feeling left behind. Another letter that takes on a more somber tone simply says,

Dear Sue'

Just say one word,

'Emily has notgrieved me'

Sign your name

to that and

I will wait for

the rest –

An editor's note with this letter mentions that "When the sheet is unfolded, it appears that Susan has signed her name to this agreement" (Open Me Carefully 157). While there is little-to-no context to this contract-letter in the collection, we can assume just based on the content that Dickinson is concerned about possibly upsetting Susan in some way and is attempting to reach out to smooth things over. Whether or not she actually had 'grieved' Susan, it is obvious that Susan was willing to move forward and that Emily's unusual attempt at an apology was effective.

A number of critics believe that Emily was in love with Susan, referencing many of the letters that Emily writes to Susan as well as the poetry she dedicated to her as evidence. An interesting example of this can be found in a piece of a letter that was written to Susan while she was one a trip. In this letter, Emily writes a letter-poem about how much Susan is loved and missed by her family, mentioning, “We remind her / we love her – / Unimportant fact, / though Dante / did’nt think so, / nor Swift, nor / Mirabeau” (Open Me Carefully 190), essentially comparing her love for Sue to “Dante’s passionate love for Beatrice, Jonathan Swift’s love of Stella, and Mirabeau’s love of Sophie de Ruffey” (Open Me Carefully 191).

A frequently-referenced Dickinson poem to indicate a romantic relationship is "Her breast is fit for pearls," which the editors of Open Me Carefully suggest was dedicated to Sue but her name "was carefully erased from the verso" (91) in the surviving copy.

At first glance, it certainly appears that Dickinson is declaring her love for Sue with the ‘Dante’ comment and in some of her other letters and poems. If I simply pay attention to the letters Dickinson wrote to Sue and ignore the commentary, I definitely notice Dickinson’s passionate emotions towards Sue and how much she obviously cares about her. However, based off of my observations from other letters Dickinson sent to other recipients she was particularly close to, passionate words and expressions of love seem to be the norm for her. For example, when she was young, she wrote a letter to a friend, stating, “How I wish you were mine, as you once were, when I had you in the morning, and when the sun went down, and was sure I should never go to sleep without a moment from you” (qtd. in Habegger 130), referencing how they shared a room together during a period of time in 1841-1842.

While I believe it is safe to conclude that Emily Dickinson felt everything intensely, including all forms of love and affection, I cannot say for sure whether Dickinson felt romantic love for Susan or for every person she wrote about in this manner. From a twenty-first century mindset, it certainly appears that Dickinson had dozens of romantic connections, but it is also important to understand that language and communication was different during this time period. For instance, sentimental novels, which were popular during Dickinson’s lifetime, are often viewed as silly and overly dramatic by modern readers due to the hyper-emotional language and content; perhaps, by the same token, our modern view of language and expression affects our view on Dickinson’s communication with different people she felt close to, causing us to read things into the letters that were not meant to be there. Either way, whether Dickinson felt romance for Sue or not, their friendship was valuable to Dickinson and helped her to grow in relation to her poetry, as well as emotionally and socially.

THOMAS WENTWORTH HIGGINSON

Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson's friendship was a unique one, and it was certainly one of the most influential friendships in both of their lives.

They originally became friends because Emily decided to send some of her poetry and a note to him, asking him if her "Verse [was] alive" (Wineapple 3). This correspondence, which eventually turned into a friendship, provided Emily with constructive feedback on her work. As he critiqued the poetry, Wineapple notes that Emily referred to his editing as “surgery” (Wineapple 7). Higginson was intrigued by Dickinson’s mysterious and secretive nature, as well as her poetry, and it blossomed into a friendship that lasted for the remainder of Dickinson’s life.

Higginson came into Emily’s life at a time where she needed a ‘breath of fresh air’ and someone to give her some perspective into the world she was separated from at the time. Emily also likely felt a sense of comradery with Higginson as a fellow writer and poet, helping her feel a stronger sense of community in that area of her life. In these letters, Dickinson maintains a more whimsical and mysterious tone than she does in her letters to Susan. Wineapple even mentions that "she liked to quote him back to himself, lobbing phrases at him in her slightly coquettish way" (146). She still mixed her poetic style into the letters and sent numerous poems for Higginson to read, but many of these letters touched on subjects that Emily did not or could not discuss with Susan or others in Amherst. Because Higginson was not a part of her family's inner circle, nor a part of their small town where everyone knew her father, Dickinson was able to open up with confessions like, “I never had a mother ... I suppose a mother is one to whom you hurry when you are troubled” (qtd. Habegger 92) without fear of it getting back to her family or neighbors.

The whimsical nature of her words certainly had an affect on Higginson, causing him to write things like, "if I could once see you & know that you are real, I might fare better" (Wineapple 167), and "It is hard [for me] to understand how you can live so alone ... with thoughts of such quality coming up in you" (167). They continued to be penpals, only ever meeting twice in person. When Higginson came for his first to visit Amherst, Emily greeted him by giving him lilies and saying, “Forgive me if I am frightened; I never see strangers & hardly know what I say” (Habegger 523). This not only shows how nervous she was to meet her friend, but it also helps us to see why writing was such a good outlet for her––in writing, she was always able to think over and edit the things she intended to say without fear of stumbling over her words.

There are some who believe that this letter-based friendship between Dickinson and Higginson was actually a romance in disguise. In a letter Higginson wrote to Dickinson before they had a chance to meet in person, he wrote, “I have the greatest desire to see you, always feeling that if I could once take you by the hand I might be something to you…” (Wineapple 163). At first glance, this comment sounds rather suggestive, making one wonder what exactly Higginson wanted to be to Dickinson. It becomes fairly apparent that Dickinson was certainly something special to HIgginson when he wrote his novel, Malbone, including a main character who “mostly sounds like Higginson himself, recast as the artist who falls in love with his fiancée’s untamed half sister, Emilia, often referred to as Emily … And it is this Emily/Emilia that is his Laura, his ideal, his symbol of the unadulterated, untrammeled pursuit of art” (Wineapple 179).

Perhaps Higginson did not love Dickinson in the traditional sense, instead viewing her as a source of mysterious, otherworldly inspiration that reminded him of ideal love. On the other hand, maybe he loved her on an intellectual level, falling for the unusual and intelligent woman he met on the pages that were sent from Amherst. Either way, there seems to be a definite sense of allure for Higginson with respect to Dickinson, and Wineapple concludes that when Higginson wrote that he was glad that they did not live near one another, it is because he found Emily “far too dangerous” (181).

On the other hand, Dickinson seems to command Higginson’s attention in her own way, continually asking him to ‘instruct’ her and ‘teach’ her and by sending poems that touched on personal subjects. Wineapple mentions an example of a poem that Dickinson sent to Higginson which he did not include in either of the posthumous collections of her work he helped to edit, noting that “maybe he thought it much too personal to share” (196). Wineapple also explains that even though Dickinson did not really need Higginson’s help to write poetry, she “coquettishly continued to ask for the advice he proffered” (191). So whether there were true feelings on either side or not, perhaps allowing Higginson to help edit her poetry was Dickinson’s way of subtly flirting with him. Perhaps Higginson and Dickinson simply loved the ideas of one another instead of the reality of one another. Both of them were poets and hopeless romantics––a common side-effect of which is falling in love too easily.

Dickinson and Higginson began to drift apart after Higginson’s sudden engagement and marriage to Mary Potter Thatcher and Dickinson’s letter-filled affair with Judge Otis Lord. According to Wineapple, after Dickinson heard about Higginson’s upcoming marriage, “it seems she considered him less accessible––even less dependable––than before” (219), noting that the number of her letters seemed to decline during this time. Perhaps some of the decline in letters to Higginson was, in part, due to Dickinson’s involvement with Judge Lord, which caused her to pen beautifully passionate words like, “I confess that I love him – I rejoice that I love him – I thank the maker of Heaven and Earth – that gave him to me to love – the exaltation floods me” (Wineapple 223). However, even though both individuals seemed to be preoccupied with their own lives at that time, the friendship between Dickinson and Higginson was not over by any means; when Mr. and Mrs. Higginson’s new baby daughter suddenly died, Dickinson was there for Higginson by doing what she did best––writing. When describing this situation, Wineapple points out that “If a gulf had opened between them, Higginson’s daughter temporarily bridged it” (226). This seems to have opened up more regular communication again, helping them to stay connected even though both of their lives were changing.

This communication between them lasted until Emily's death in 1886. Higginson attended her funeral and facilitated the publication of her poems in 1890.

"MASTER"

Another interesting collection of letters that has posed quite a mystery to Dickinson scholars are the group of Dickinson’s strangely passionate letters to someone she calls “Master.” These letters to “Master” mark a change in Dickinson’s writing, entering into a deeper kind of passion than some of her earlier work, making bold statements like, “Open your life wide, and take me in forever” (Wineapple 72), "I am older – tonight, Master – but the love is the same" (Wineapple 72), "What would you do with me if I came 'in white'?" (Wineapple 73).

The odd thing is, historians are currently unsure of "Master's" identity. Several people have been suggested as being this nameless recipient, but "the reining hypothesis is that the Master was the Reverend Charles Wadsworth" (Wineapple 71).

In these letters, Dickinson reveals another very raw side of herself, dropping all sense of subtlety or coquettishness. She bluntly communicates how her "Master" is inflicting pain on her, referring to herself as a Daisy:

If you saw a bullet

hit a Bird – and he told youhe was'nt shot – you might weepat his courtesy, but you wouldcertainly doubt his word –One drop more from the gashthat stains your Daisy'sbosom – then would you believe?

Dickinson, Emily. Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson's Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson. Edited by Martha Nell Smith, and Ellen Louise Hart. Paris Press, 1998.

Habegger, Alfred. My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: the Life of Emily Dickinson. Modern Library, 2002.

Wineapple, Brenda. White Heat: the Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Anchor Books, 2009.